Using Data Science to unravel Einstein's Cosmic Clues: Discovering Time Bends in Celestial Duets

In this project, I analysed 13 years (several TBs) of time-series data and employed statistical techniques to detect Einstein's relativistic effect (Shapiro Delay) in a Neutron Star-White Dwarf star system.

For the curious readers!

What are Neutron Stars?

→ Neutron stars are the remnants of massive stars that have undergone a supernova explosion. These incredibly dense objects, packing more mass than our Sun into a city-sized radius, exhibit fascinating properties, including strong gravitational fields and unique behaviors under extreme conditions.

→ Pulsars are rapidly rotating neutron stars that emit strong radition from their magnetic poles. Due to their rotation these radiation appear to be pulsating to us.

How do we use them to test Eintein's theory of relativity?

→ The radiation from these rotating stars experience extreme gravity of the star system and it is delayed in its arrival time on Earth due to multiple effects including gravitational time dilation.

→ Through the exact measurement of the arrival times of these pulses of radiation, we are able to measure various phenomena affecting the pulse on its passage to the Earth including various effects implied by Einstein's Theory of General Relativity.

Aim

To find hidden patterns indicating a relativistic effect and measure the effects that govern the motion of both the stars in the long-term data.

Data

- More than 10's of TBs of data was collected for this project with the Green Bank, Parkes, and MeerKAT Radio Telescopes and the Fermi Gamma-ray space telescope over the last 13 years.

- All the data was first down-sampled and converted to a consistent frequency and time resolution.

- Data Cleaning was performed with a data reduction pipeline that cleans Radio frequency interferances (RFI) - strong radio signals coming from the Earth itself- from the data by determining anomalies using different statistical metrics including standard deviation, mean, range, and maximum amplitude of the Fourier transform of the mean-subtracted residuals.

- Further residual strong RFIs were also removed manually for each data-set.

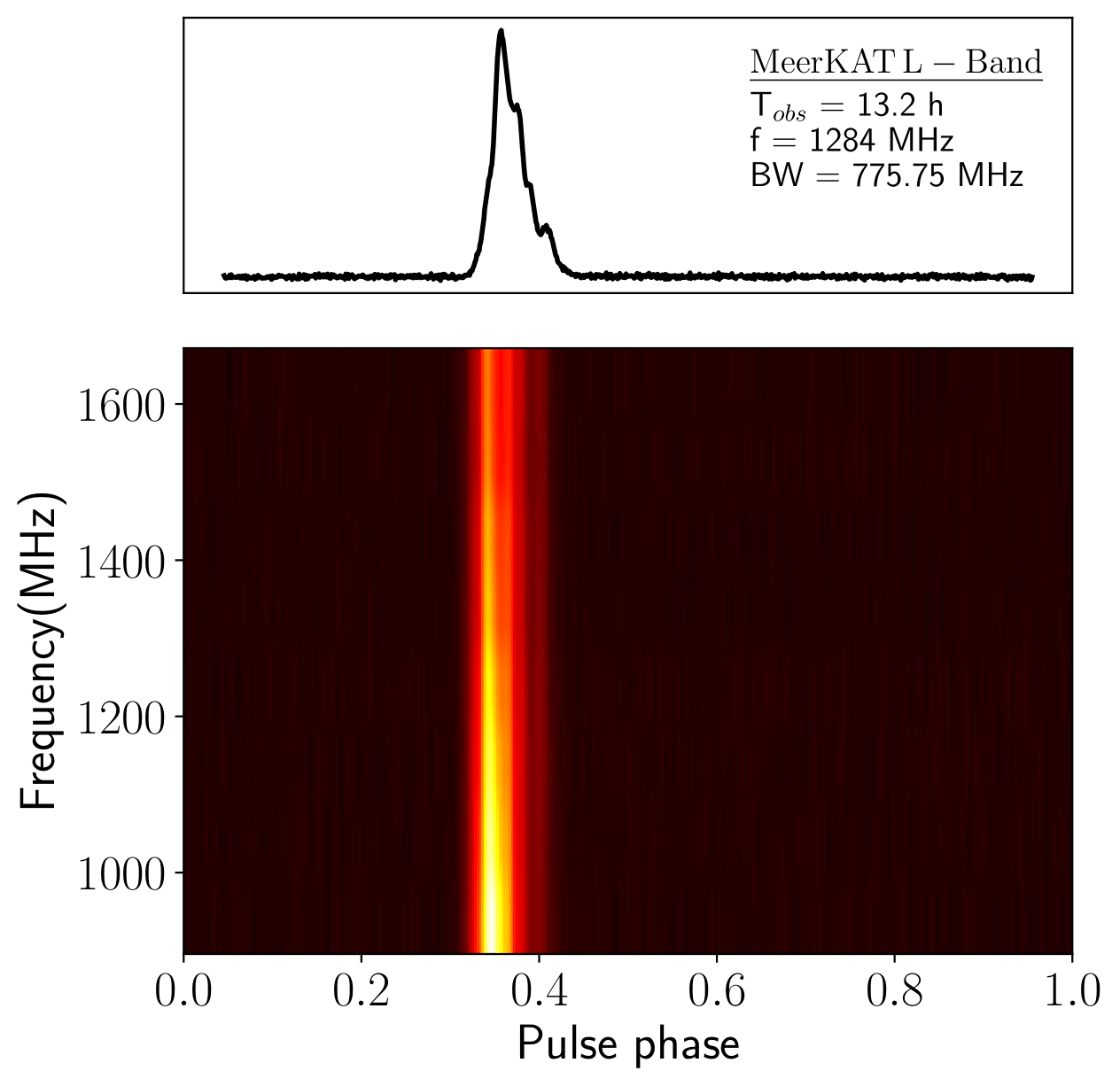

- To improve the Signal-to-Noise Ratio of each of the pulse profiles (Intensity vs rotational phase of the Neutron star), further downsampling was performed manually.

- A standard template was first chosen by implementing various downsampling and averaging techniques for each data set and determining the best reduced chi-square for the fit with the data.

- Accurate Times of Arrival which are the time-stamps of each integrated pulse profile with a common reference are then calculated by doing the cross-correlation of the each cube of data with its respective standard template.

- A scaling factor was then used to re-scale the uncertainties of ToAs to account for the un-modelled systematic effects in the data. This factor ensures conservative estimates of the uncertainties of the parameters. This is factor determined from the reduced chi-square of the whole data set.

- To fit the data and find the best model parameters, we use a binary model called ELL1H+ model, this model is especially useful to avoid correlation between two parameters (T0 and w) in low-eccentricity binaries. It re-parameterises the existing model and fits for Tasc, and two Laplace-Lagrange parameters (epsilon1 and epsilon2). This model also includes a higher order term for eccentricity in the expansion of Romer delay.

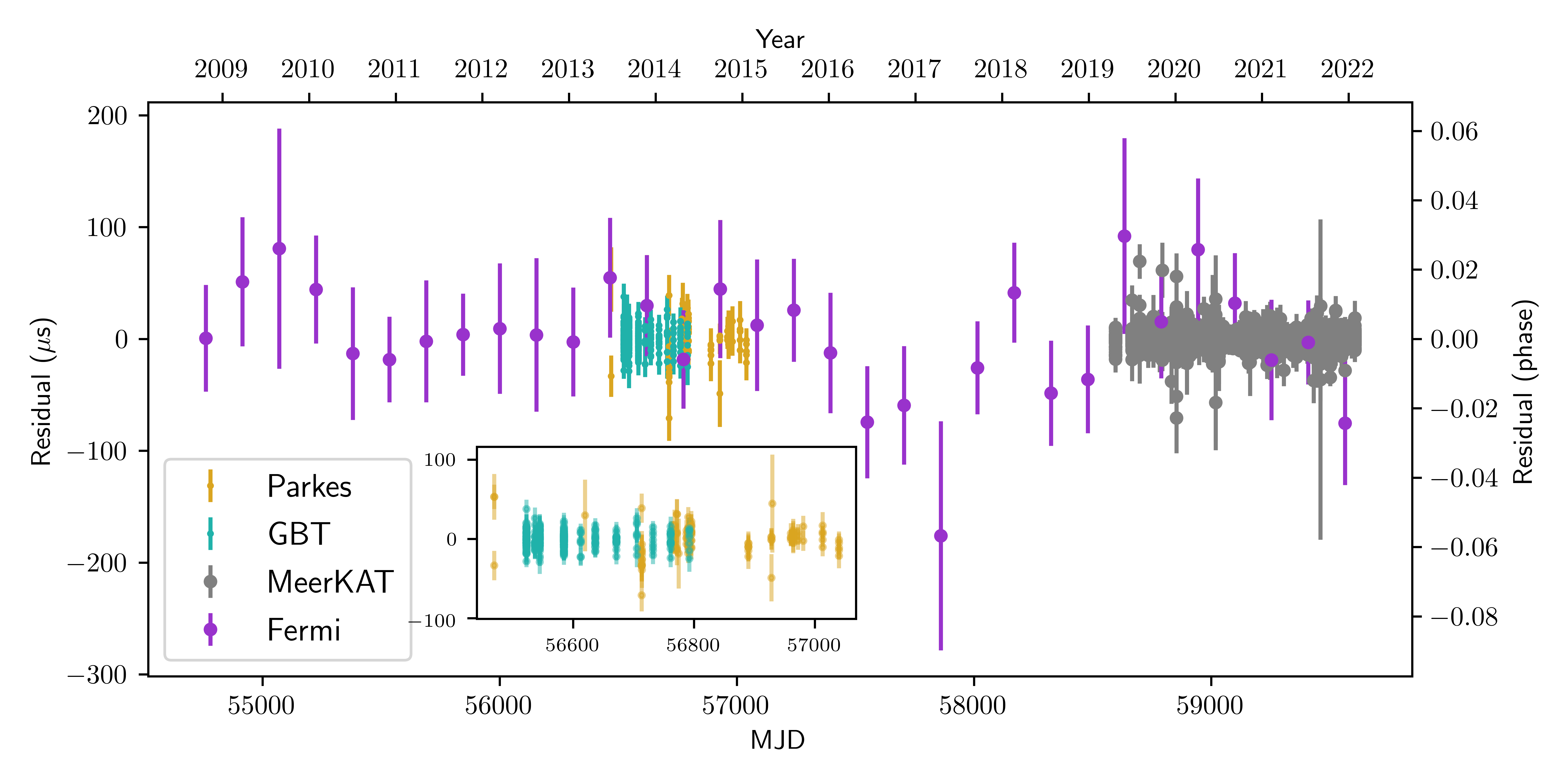

- From the fit of ELL1H+ binary model on all the radio and gamma-ray data, we derived a phase-connected timing solution for this system. This is a unique solution of the binary that correctly predicts the pulse arrival times for every rotation of the pulsar in the data-set. Below figure shows the post-fit ToA residuals as a function of time.

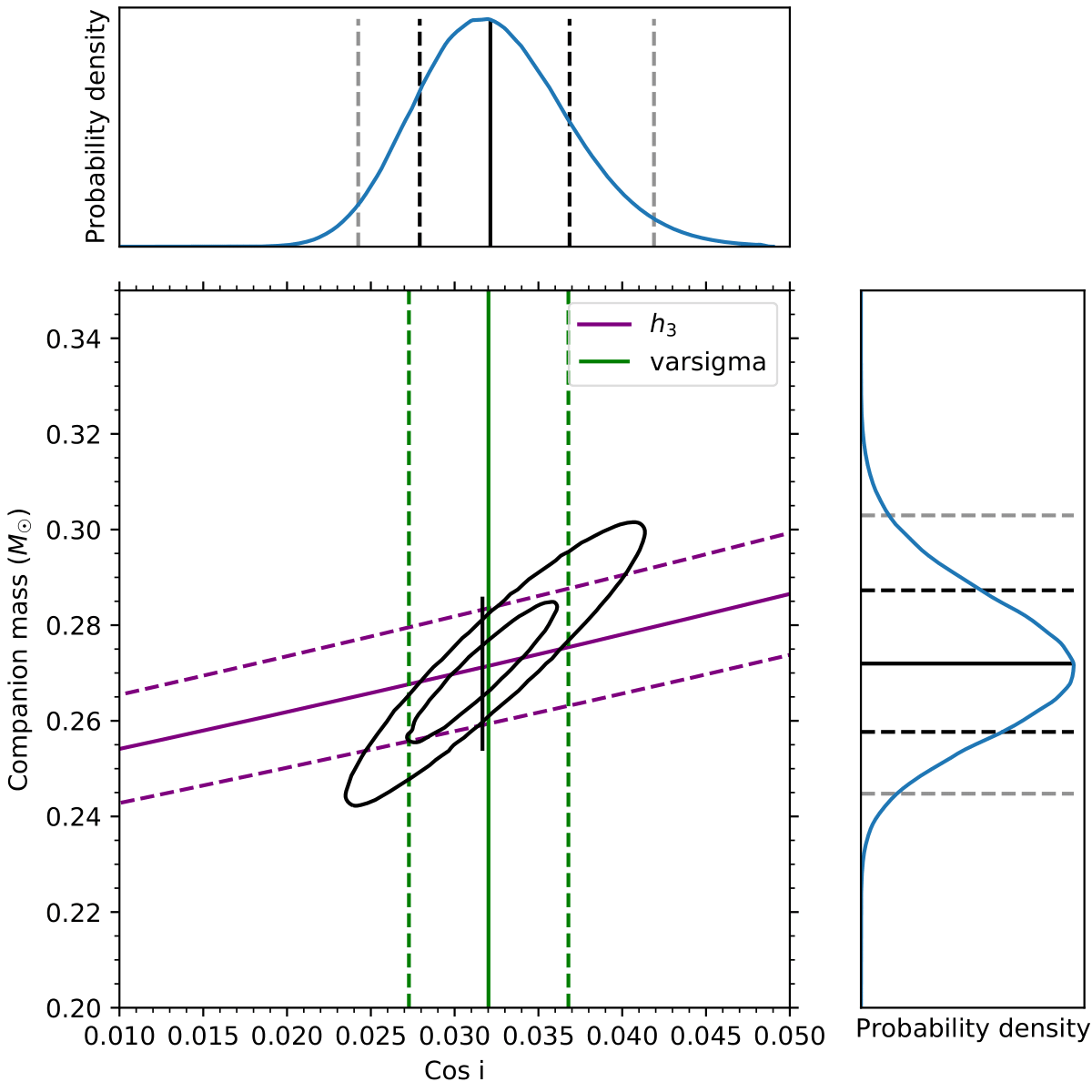

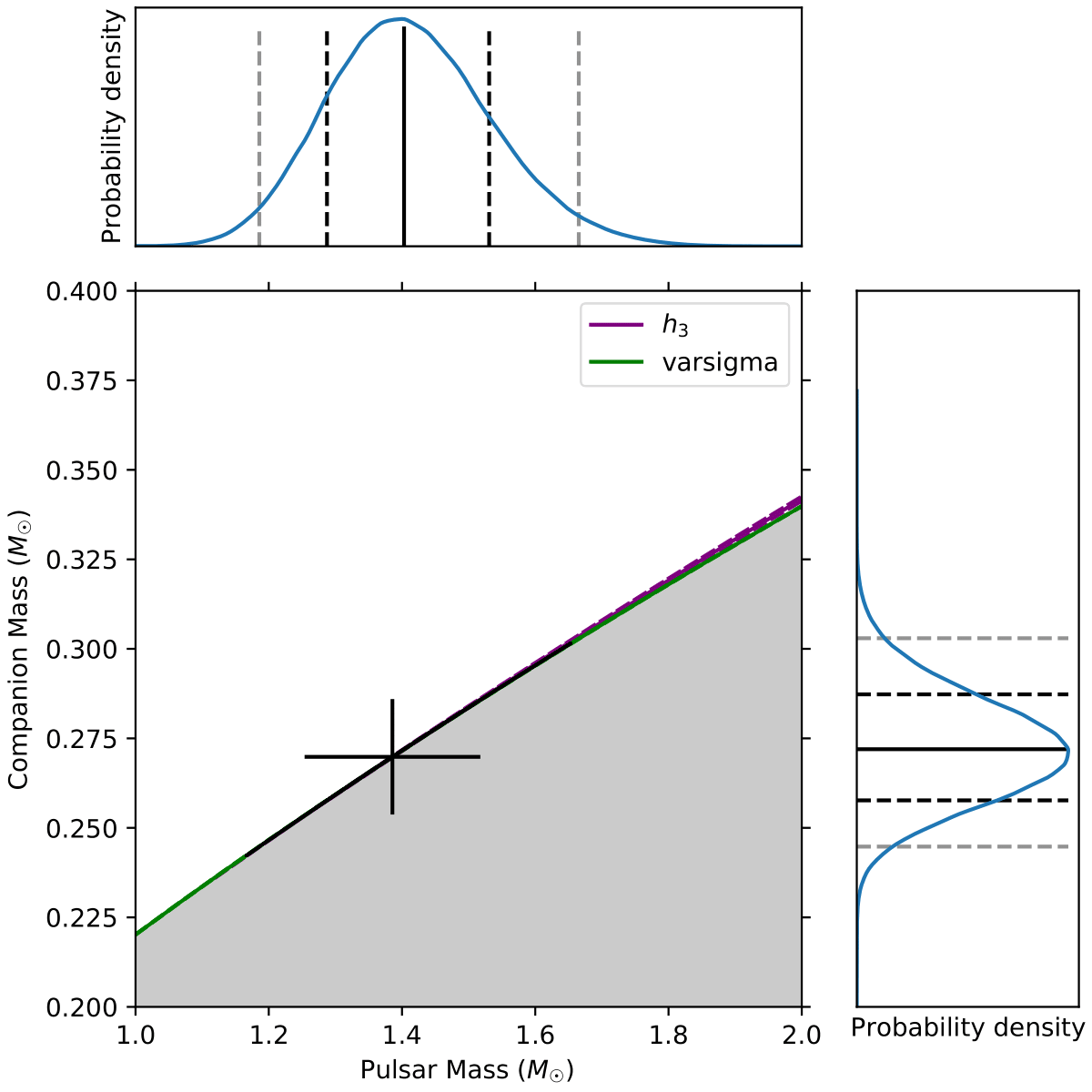

- First, we created a uniform grid of points on the (cos𝑖 − 𝑀c) plane and derived the best-fit 𝜒2 values from the fit of this model on each of the points in this grid.

- Second, these 𝜒2 values are then converted to a Bayesian likelihood using the relation by Splaver et al. (2002). The likelihoods are then used in the calculation of joint posterior probability density functions (PDFs), both in the original plane and also in the (𝑀p − 𝑀c) plane.

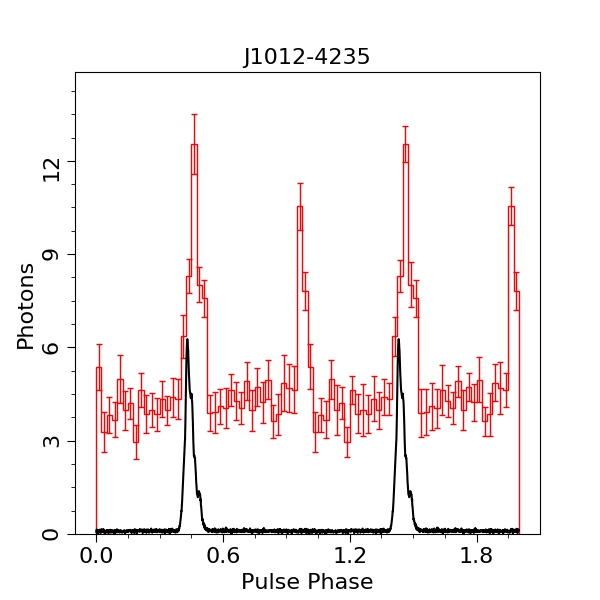

Intensity and frequency of the pulse profile of PSR J1012-4235 plotted as a function of pulse phase.

Pre-processing

Data Analysis

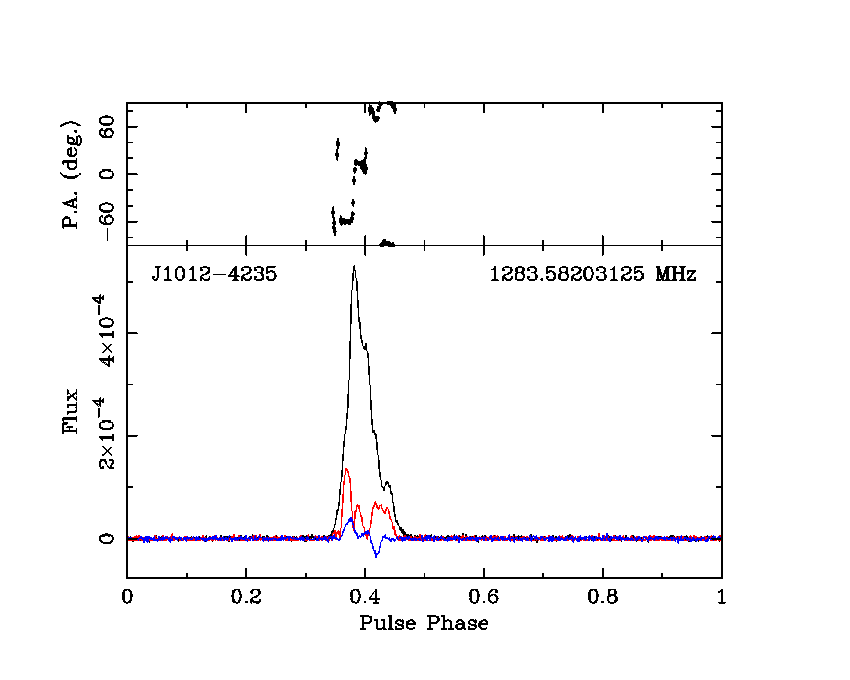

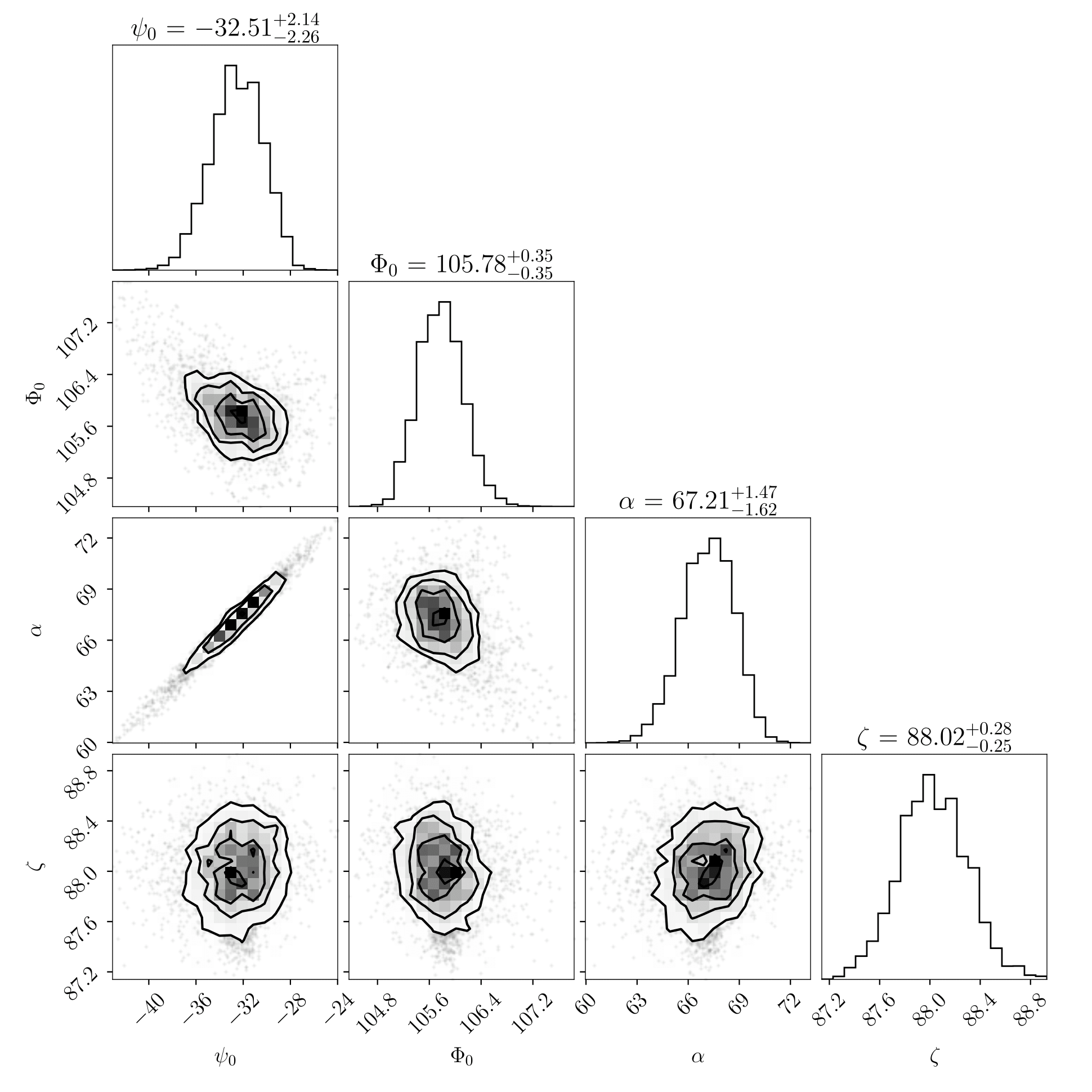

Fitting rotating vector model

To determine the Geometry of the system (its orientation), we perform a fit of the Rotating Vector Model (RVM) to the polarisation profile of the pulsar. The fit implies that the pulsar is likely not an orthogonal rotator and this explains why we do not see any inter-pulse in the pulse profile.

Timing Analysis:

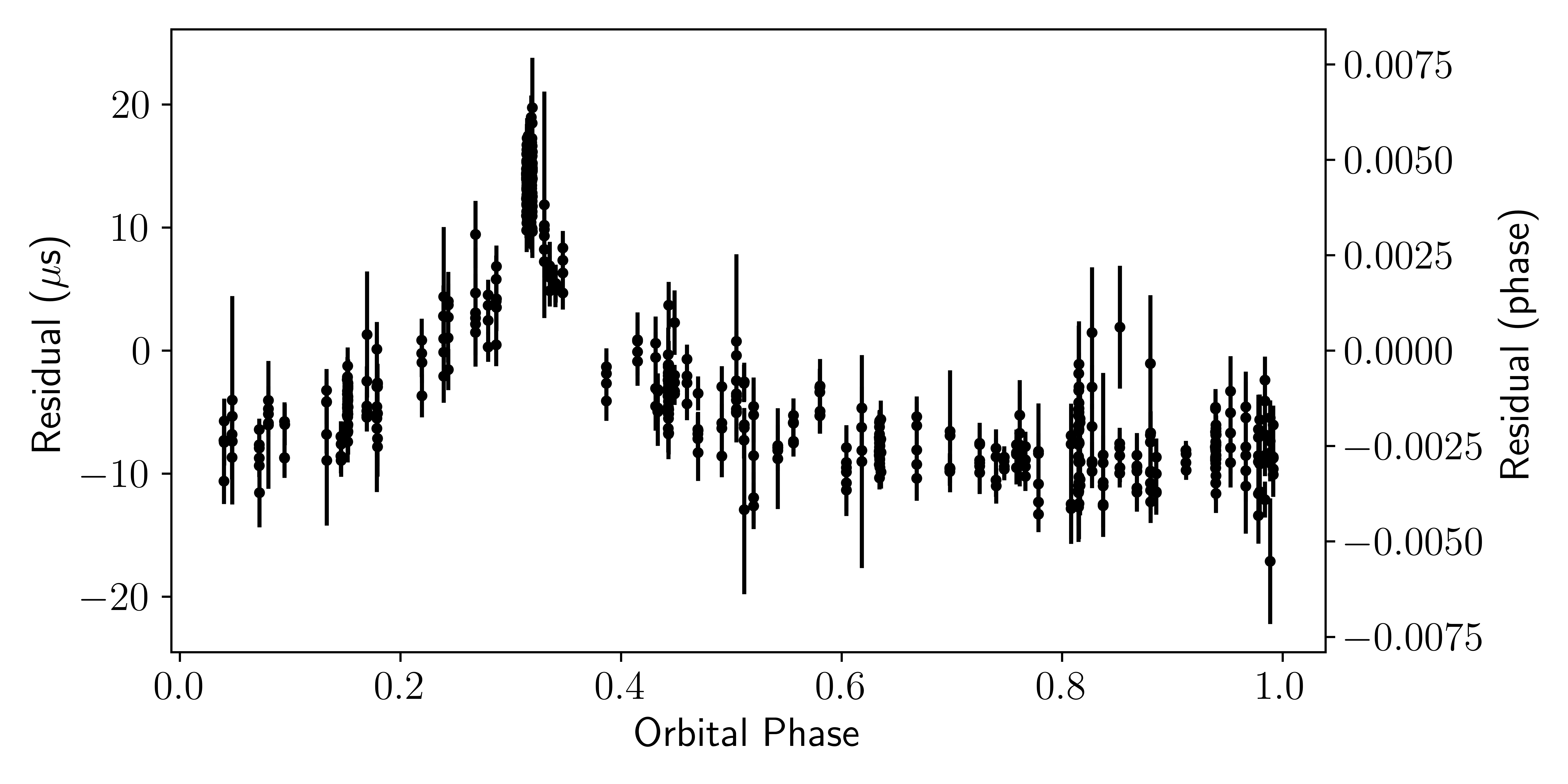

We were able to successfully measure the best-fit solution of the binary and astrometric parameters. We also measured, for the first time, the parallax of the system. We find a strong detection of Shapiro Delay- a time dilation effect on the light emitted from pulsar due to its passage from the gravitational potential of it's companion star. We measure 20-sigma and 200-sigma detection of the two of its parameters. Following figure shows a typical shapiro delay signature, with enhanced amplitude at the place where companion passes in front of the neutron star (and thus the region where light gets delayed, affected by time dilation).

Comparing Gamma-ray and radio pulse profiles

Unlike in radio, we do see a second peak in the pulsed emission, which is superficially consistent with the previously mentioned idea of the orthogonal rotator. However, the pulse morphology seen here is similar to that of most 𝛾-ray pulsars (Smith et al. 2023), where a single radio pulse is followed, after a small offset in phase (which is visible here) by two strong peaks in the 𝛾-ray emission, linked by a bridge of emission, which is also faintly visible here. This is clear evidence for the fact that the radio and gamma-ray emission do not generally originate in the same region of the pulsar magnetosphere.

Determination of the masses

In order to better understand the correlations between the Shapiro delay parameters and better estimate their uncertainties and the uncertainties on the masses and orbital inclination, we performed Bayesian study of the masses and orbital inclination of the system.

Below, we plot the Shapiro delay parameters derived from the ELL1H+ model on the (cos𝑖 − 𝑀c) and (𝑀p − 𝑀c) planes, the black contours represent the 39% (inner) and 85% (outer) confidence ellipses on the joint posterior pdfs, which essentially represent the 1-𝜎 and 2-𝜎 error bars in 1-D PDFs. The corner plots show the marginalised 1-D posterior PDFs for 𝑀c, 𝑀p, and cos𝑖. The vertical lines in these plots represent the median, 1-𝜎, and 2-𝜎-equivalent percentiles for each of these parameters.

For exact values and uncertainties of the parameters, please see the paper here.

Determination of Kinematic effects

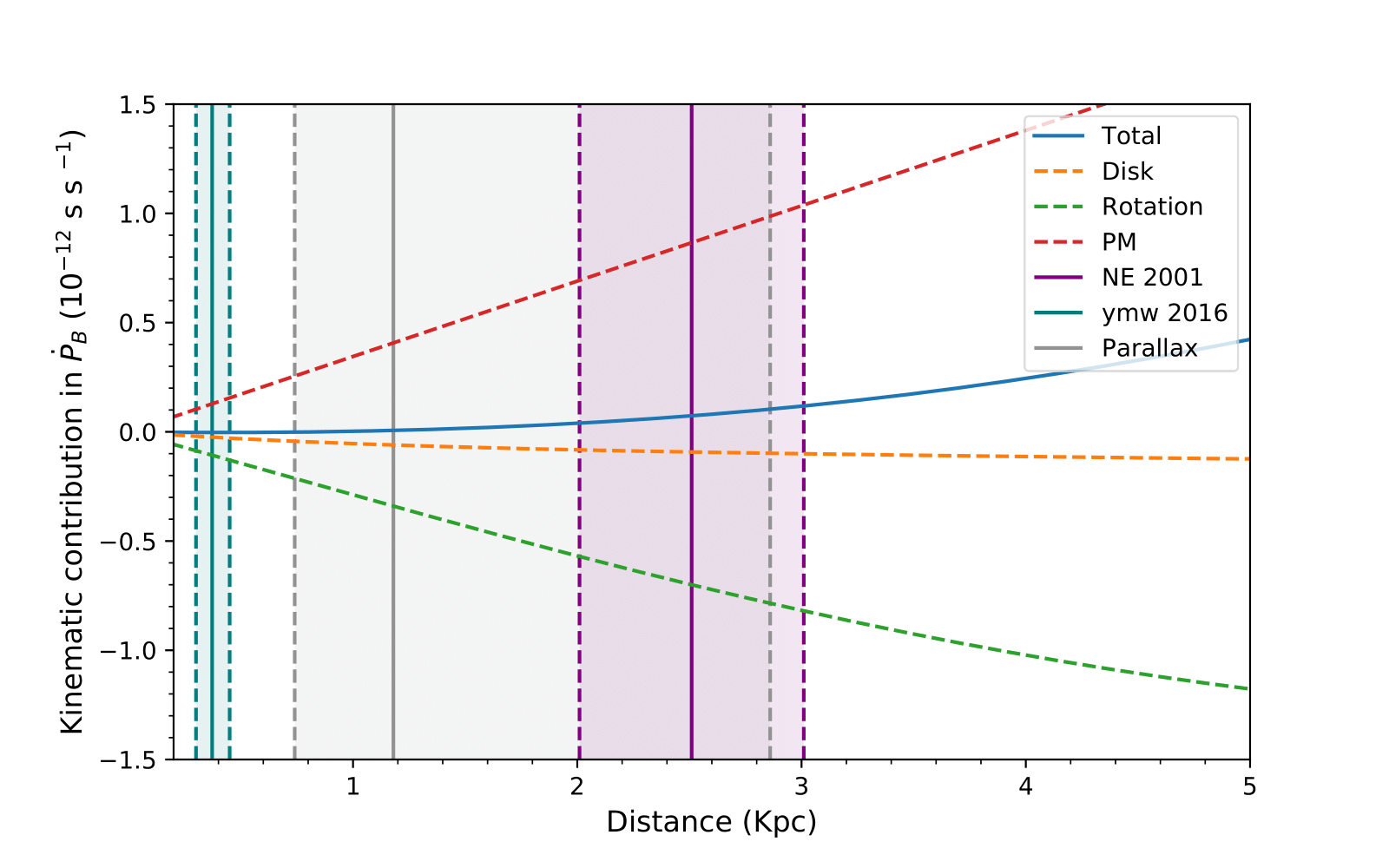

Acceleration contributions to orbital period derivative due to kinematic effects as a function of distance. Orange and green curves show the vertical and differential accelerations from galactic disc while red curve shows the contribution from proper motion of the pulsar. Blue curve represents the total acceleration contribution. Distance uncertainty of 20% is assumed on the DM distance predictions from NE2001 model (purple shaded region) and YMW16 model (teal shaded region) while 1-𝜎 uncertainty is shown for the parallax measurement from timing (gray shaded region).

As we can see, the total contribution to observed orbital period derivative from the kinematic effects (blue curve) is extremely flat. This turns out to be one of the most interesting features of this system. Even with the relatively large distance uncertainty, this contribution is not only small but it has a small associated uncertainty. This has an important consequence: we will be able to obtain a tight constraint on the variation of the gravitational constant.

Conclusion

PSR J1012−4235 is a 3.1-ms pulsar in a wide binary (37.9 days) with a white dwarf companion. We detected, for the first time, a strong relativistic Shapiro delay signature in PSR J1012−4235. Our detection is a result of the timing analysis of data, spanning 13 years, collected with the Green Bank, Parkes, and MeerKAT Radio Telescopes and the Fermi 𝛾-ray space telescope. We measured the orthometric parameters for Shapiro delay and obtain a 22-𝜎 detection of ℎ3 parameter of 1.222(54) μs and a 200-𝜎 detection of 𝜍 of 0.9646(49). With the assumption of general relativity, these measurements constrained the pulsar mass (𝑀p = 1.44+0.13 −0.12 Msolar), the mass of the white dwarf companion (𝑀c = 0.270+0.016 −0.015 Msolar) and the orbital inclination (𝑖 = 88.06+0.28 −0.25) deg. Including the early 𝛾-ray data in our timing analysis facilitated a precise measurement of the proper motion of the system of 6.58(5) mas yr−1 . We also showed that the system has an unusually small kinematic corrections to the measurement of orbital period derivative, thus it has the potential to yield stringent constraints on the variation of the gravitational constant in the future.